SUN. AUG. 15 [EVERY SUNDAY]

3 PM FREE RAW VEGAN PREPARATION DEMONSTRATION

AND HOW TO BECOME OPTIMALLY HAPPY, HEALTHY & WEALTHY

138 SAINT JAMES PLACE BKLYN

RSVP DR. NATURAL 718-783-3465 / 347-760-8147

SUN. AUG. 15 [EVERY SUNDAY]

3 PM FREE RAW VEGAN PREPARATION DEMONSTRATION

AND HOW TO BECOME OPTIMALLY HAPPY, HEALTHY & WEALTHY

138 SAINT JAMES PLACE BKLYN

RSVP DR. NATURAL 718-783-3465 / 347-760-8147

CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THIS WEEKEND

RSVP 718-783-3465 / 347-760-8147 DR. NATURAL

JOIN WWW.TEMPLEOFILLUMINATION.NING.COM

RSVP FOR BLACKVEG FEST

SAT. AUG. 14 12 PM - 5 PM

LINCOLN TERRACE PARK BKLYN

6 PM CONCERT

PROSPECT PARK BANDSHELL

SUN. AUG. 15 [EVERY SUNDAY]

3 PM FREE RAW VEGAN PREPARATION DEMONSTRATION AND HOW TO BECOME OPTIMALLY HAPPY, HEALTHY & WEALTHY 138 SAINT JAMES PLACE BKLYN

SUN. AUG. 15 6 PM CONCERT

CENTRAL PARK SUMMERSTAGE

CALL DR. NATURAL 718-783-3465 / 347-760-8147

Fri, Aug 13 at 7:30-10:30 PM

Brooklyn, NY, USA

FRIDAY, AUGUST 13Doors 6:30 / Show 7:30

SKIP MARLEY, the grandson of the reggae legend, has carved out a unique space for himself in the music world with an energetic blend of rock, rap, and pop and collaborations with the likes of HER, Rick Ross, and Ari Lennox. The Philly-based rapper and producer IVY SOLE, who emerged from the collectives Indigold, Liberal Art, and Third Eye Optiks, kicks things off.

To learn more about our COVID-Safety precautions, visit our FAQ page.

We are a leading arts and media institution anchored in Downtown Brooklyn whose work spans contemporary visual and performing arts, media, and civic action. For over forty years, our institution has shaped Brooklyn's cultural and media landscape by presenting and incubating artists, creators, students, and media makers. As a creative catalyst for our community, we ignite learning in people of all ages and centralize diverse voices that take risks and drive culture forward. BRIC is building Brooklyn's creative future.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

The Roots

THURSDAY, AUGUST 12

Doors 6:00 PM / Show 7:00 PM

*Ticketed Benefit Concert*

The legendary Roots Crew have become one of the best known and most respected hip-hop acts in the business, winning four GRAMMYS, including "Best R&B Album" for Wake Up!, "Best Traditional R&B Vocal Performance" for "Hang in There" (with John Legend) and "Best Group or Duo R&B Vocal Performance" for "Shine." This brings the band's GRAMMY nomination count to twelve. Additionally, "The Roots Picnic," a yearly star-studded mix of musicians, has become a celebrated institution. The Roots were named one of the greatest live bands around by Rolling Stone and serve as the official house band on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Recently, Black Thought and Questlove have been the executive producers of the acclaimed documentary series “Hip-Hop: The Songs That Shook America” on AMC. Felicia Temple will join as an opening act.

Vegan nutrition refers to the nutritional and human health aspects of vegan diets. A well-planned, balanced vegan diet is suitable to meet all recommendations for nutrients in every stage of human life.[1] Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fiber, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals; and lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[2] Researchers agree that those on a vegan diet should eat foods fortified with vitamin B12 or take a dietary supplement.[1][3] Preliminary evidence from epidemiological research indicates that a vegan diet may lower the risk of cancer.[4]

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Dietitians of Canada state that properly planned vegan diets are appropriate for all life stages, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence.[5][6] They indicate that vegetarian diets may be more common among adolescents with eating disorders, but that its adoption may serve to camouflage a disorder rather than cause one. The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council similarly recognizes a well-planned vegan diet as viable for any age,[7][8] as does the New Zealand Ministry of Health,[9] British National Health Service,[10] British Nutrition Foundation,[11] Dietitians Association of Australia,[12] United States Department of Agriculture,[13] Mayo Clinic,[14] Canadian Pediatric Society,[15] and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.[16] The British National Health Service's Eatwell Plate allows for an entirely plant-based diet,[17] as does the United States Department of Agriculture's (USDA) MyPlate.[18][19] The USDA allows tofu to replace meat in the National School Lunch Program.[20] The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics adds that well-planned vegan diets are also appropriate for older adults and athletes.[1]

The German Society for Nutrition does not recommend a vegan diet for babies, children and adolescents, or for pregnancy or breastfeeding, citing insufficient data for these subpopulations.[21]

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics stated that "plant-based eating is recognized as not only nutritionally sufficient but also as a way to reduce the risk for many chronic illnesses", including cancer.[22][1] Kaiser Permanente, the largest healthcare organization in the United States, has written, "Research shows that plant-based diets are cost-effective, low-risk interventions that may lower body mass index, blood pressure, HbA1C, and cholesterol levels. They may also reduce the number of medications needed to treat chronic diseases and lower ischemic heart disease mortality rates."[23]

There is inconsistent evidence for vegan diets providing a protective effect against metabolic syndrome.[24] Vegan diets appear to help weight loss, especially in the short term.[25] There is some tentative evidence of an association between vegan diets and a reduced risk of cancer.[26] In general the association of a vegan diet and lower cancer incidence is the same as for other types of vegetarian diet, except for prostate cancer where the association of reduced risk is stronger for a vegan diet.[27] A vegan diet offers no benefit over other types of healthy diet in helping with high blood pressure. For individuals with systolic blood pressure of 130 mmHg or higher, there is, as of 2019, tentative evidence that a vegan diet could result in an additional 4-mmHg reduction in blood pressures.[28]

However, consuming no animal products increases the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency which occurs in up to 80% of vegans that do not supplement with vitamin B12.[29] Vegans are at risk of low bone mineral density without appropriate intake of calcium.[30]

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Dietitians of Canada consider well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets "appropriate for individuals during all stages of the lifecycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, and adolescence, and for athletes". The German Society for Nutrition cautioned against a vegan diet for babies, children, and adolescents, and during pregnancy and breastfeeding, due to insufficient data.[31][21] The position of the Canadian Pediatric Society is that "well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets with appropriate attention to specific nutrient components can provide a healthy alternative lifestyle at all stages of fetal, infant, child and adolescent growth. It is recommended that attention should be given to nutrient intake, particularly protein, vitamins B12 and D, essential fatty acids, iron, zinc, and calcium.[15]

According to a 2015 systematic review, there was little evidence available about vegetarian and vegan diets during pregnancy, and a lack of randomized studies meant that the effects of diet could not be distinguished from confounding factors.[32] It concluded: "Within these limits, vegan-vegetarian diets may be considered safe in pregnancy, provided that attention is paid to vitamin and trace element requirements."[32] A daily source of vitamin B12 is important for pregnant and lactating vegans, as is vitamin D if there are concerns about low sun exposure.[33] A different review found that pregnant vegetarians consumed less zinc than pregnant non-vegetarians, with both groups' intake below recommended levels; however, the review found no significant difference between groups in actual zinc levels in bodily tissues, nor any effect on gestation period or birth weight.[34]

Researchers have reported cases of vitamin B12 deficiency in lactating vegetarian mothers that were linked to deficiencies and neurological disorders in their children.[35][36] It is recommended that a doctor or registered dietitian should be consulted about taking supplements during pregnancy.[37][38]

Vegan diets have attracted negative attention from the media because of cases of nutritional deficiencies that have come to the attention of the courts, including the death of a baby in New Zealand in 2002 due to hypocobalaminemia, i.e. vitamin B12 deficiency.[39][40]

The American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics states that special attention may be necessary to ensure that a vegan diet will provide adequate amounts of vitamin B12, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, iron, and zinc.[1] These nutrients are available in plant foods, with the exception of vitamin B12, which can be obtained only from B12-fortified vegan foods or supplements.[41] Iodine may also require supplementation, such as using iodized salt.[1]

Vitamin B12 is not made by plants or animals, but by bacteria that grow in soil, feces, dirty water, the intestines of animals or laboratories,[42][43][44][45][46] so plant foods are not reliable sources of B12.[47] It is synthesized by some gut bacteria in humans and other animals, but humans cannot absorb the B12 made in their guts, as it is made in the colon which is too far from the small intestine, where absorption of B12 occurs.[48] Ruminants, such as cows and sheep, absorb B12 produced by bacteria in their guts.[48]

Animals store vitamin B12 in liver and muscle and some pass the vitamin into their eggs and milk; meat, liver, eggs and milk are therefore sources of B12.[49][50]

The UK Vegan Society, the Vegetarian Resource Group, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, among others, recommend that every vegan consume adequate B12 either from fortified foods or by taking a supplement.[51][52][53][54]

Vitamin B12 deficiency is potentially extremely serious, leading to megaloblastic anemia (an undersupply of oxygen due to malformed red blood cells),[55] nerve degeneration and irreversible neurological damage.[56] Because B12 is stored in large amounts in the liver, deficiency in adults may begin only years after adoption of a diet lacking B12. For infants and young children who have not built up these stores, onset of B12 deficiency can be faster and supplementation for vegan children is thus crucial.

Evidence shows that vegans who are not taking vitamin B12 supplements do not consume sufficient B12 and often have abnormally low blood concentrations of vitamin B12.[57] This is because, unless fortified, plant foods do not contain reliable amounts of active vitamin B12. Vegans are advised to adopt one of the following dietary options:[58]

B12 is more efficiently absorbed in small regular doses, which explains why the quantity required rises so quickly as frequency goes down.

The US National Institutes of Health recommends B12 intake in a range from 0.4 micrograms a day for infants, to 2.4 micrograms for adults, and up to 2.8 micrograms for nursing mothers. [59] The European Food Safety Authority set the Adequate Intake at 1.5 micrograms for infants, 4 micrograms for children and adults, and 4.5 and 5 micrograms during pregnancy and nursing.[60] These amounts can be obtained by eating B12 fortified foods, which include some common breakfast cereals, soy milks, and meat analogues, as well as from common multivitamins such as One-A-Day. Some of the fortified foods require only a single serving to provide the recommended B12 amounts. [61]

Other B12 fortified foods may include some almond milks, coconut milks, other plant milks, nutritional yeast, vegan mayonnaise, tofu, and various types and brands of vegan deli slices, burgers, and other veggie meats.

It has been suggested that nori (an edible seaweed), tempeh (a fermented soybean food), and nutritional yeast may be sources of vitamin B12.[62][63] In 2016, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics stated that nori, fermented foods (such as tempeh), spirulina, chlorella algae, and unfortified nutritional yeast are not adequate sources of vitamin B12 and that vegans need to consume regularly fortified foods or supplements containing B12. Otherwise, vitamin B12 deficiency may develop, as has been demonstrated in case studies of vegan infants, children, and adults.[64]

Vitamin B12 is mostly manufactured by industrial fermentation of various kinds of bacteria, which make forms of cyanocobalamin, which are further processed to generate the ingredient included in supplements and fortified foods.[65][66] A Pseudomonas denitrificans strain was most commonly used as of 2017.[67][68] It is grown in a medium containing sucrose, yeast extract, and several metallic salts. To increase vitamin production, it is supplemented with sugar beet molasses, or, less frequently, with choline.[67] Certain brands of B12 supplements are certified vegan.[69]

Humans require iodine for the production of thyroid hormones that enable normal thyroid function.[70] Iodine supplementation may be necessary for vegans in countries where salt is not typically iodized, where it is iodized at low levels, or where, as in Britain and Ireland, dairy products are relied upon for iodine delivery because of low levels in the soil.[71] Iodine can be obtained from most vegan multivitamins or regular consumption of seaweeds, such as kelp.[72]

One study reported a "potential danger of iodine deficiency disorders due to strict forms of vegetarian nutrition, especially when fruits and vegetables grown in soils with low [iodine] levels are ingested."[73] Vegan diets typically require special attention for iodine, for which the only substantial and reliable vegan sources are sea vegetables, iodized salt and supplements. The iodine content of sea vegetables varies widely and may provide more than the recommended upper limit of iodine intake.[1]

Proteins are composed of amino acids. Vegans obtain all their protein from plants, omnivores usually a third, and ovo-lacto vegetarians half.[74] Sources of plant protein include legumes such as soy beans (consumed as tofu, tempeh, textured vegetable protein, soy milk, and edamame), peas, peanuts, black beans, and chickpeas (the latter often eaten as hummus); grains such as quinoa, brown rice, corn, barley, bulgur, and wheat (the latter eaten as bread and seitan); and nuts and seeds. Combinations that contain high amounts of all the essential amino acids include rice and beans, corn and beans, and hummus and whole-wheat pita.[75] In 2012, the United States Department of Agriculture stated that soy protein (tofu) may replace meat protein in the National School Lunch Program.[20]

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics said in 2009 that a variety of plant foods consumed over the course of a day can provide all the essential amino acids for healthy adults, which means that protein combining in the same meal is generally not necessary.[76] The Dietitian's Guide to Vegetarian Diets writes that there is little reason to advise vegans to increase their protein intake; but erring on the side of caution, the authors recommend a 25 percent increase over the RDA for adults, to 1 g/kg (15gr/lb) of body weight.[77]

Major vegan sources of the essential omega-3 fatty acid ALA include walnuts, flaxseeds and flaxseed oil, canola (rapeseed) oil, algae oil, hempseeds and hempseed oil, olive oil, and avocado.[1]

Diets without seafood are lower in non-essential long-chain omega-3 fatty acids like DHA and EPA. Short-term supplemental ALA has been shown to increase EPA levels, but not DHA levels, suggesting limited conversion of the intermediary EPA to DHA.[78] DHA supplements derived from DHA-rich microalgae are available, and the human body can also convert DHA to EPA.[79] Although omega-3 has previously been thought useful for helping alleviate dementia, as of 2016, there is no good evidence of effectiveness.[80]

While there is little evidence of adverse health or cognitive effects due to DHA deficiency in adult vegetarians or vegans, fetal and breast milk levels remain a concern.[78] EPA and DHA supplementation has been shown to reduce platelet aggregation in vegetarians, but a direct link to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, which is already lower for vegetarians, has yet to be determined.[81]

It is recommended that vegans eat three servings per day of a high-calcium food, such as fortified plant milks, green leafy vegetables, seeds, tofu, or other calcium-rich foods, and take a calcium supplement as necessary.[1][82]

A 2009 study of bone density found the bone density of vegans was 94 percent that of omnivores, but deemed the difference clinically insignificant.[83]

Calcium is one component of the most common type of human kidney stones, calcium oxalate. Some studies suggest that people who take supplemental calcium have a higher risk of developing kidney stones, and these findings have been used as the basis for setting the recommended daily intake (RDI) for calcium in adults.[84][85][86]

Calcium intake through food sources is preferred over supplementation given inconclusive but growing evidence to suggest that supplementation carries no health benefit or might be harmful.[87]

It is recommended for vegans to eat iron-rich foods and vitamin C daily.[88] In several studies, vegans were not found to suffer from iron-deficiency any more than non-vegans.[89][90][91][92] However, due to the low absorption rate on non-heme iron it is recommended to eat dark leafy greens (and other sources of iron) together with sources of Vitamin C.[93] Iron supplementation should be taken at different times to other supplements with a 2+ valence (chemistry) such as calcium or magnesium, as they inhibit the absorption of iron.[94]

Iron and the zinc levels of vegans may be of concern because of the limited bioavailability of these minerals. There are concerns about the bioavailability of iron from plant foods, assumed by some researchers to be 5–15 percent compared to 18 percent from a non-vegetarian diet.[95] Iron-deficiency anemia is found as often in non-vegetarians as in vegetarians, and vegetarians' iron stores are lower.[96]

Due to the lower bioavailability of iron from plant sources, the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences established a separate RDA for vegetarians and vegans of 14 mg (¼gr) for vegetarian men and postmenopausal women, and 33 mg (½gr) for premenopausal women not using oral contraceptives.[97]

High-iron vegan foods include soybeans, blackstrap molasses, black beans, lentils, chickpeas, spinach, tempeh, tofu, and lima beans.[98][99] Iron absorption can be enhanced by eating a source of vitamin C at the same time,[100] such as half a cup of cauliflower or five fluid ounces of orange juice. Coffee and some herbal teas can inhibit iron absorption, as can spices that contain tannins such as turmeric, coriander, chiles, and tamarind.[99]

Some news reports presented vegan diets as deficient in choline following an opinion piece in the BMJ by a nutritionist affiliated with the meat industry.[101][102][103] Although many animal products, like liver and egg, contain high amounts of choline (355 mg/3 oz and 126 mg/large egg, respectively), wheat germ (172 mg/cup), Brussels sprouts (63 mg/cup), and broccoli (62 mg/cup) are also good sources of choline.[104] Other sources are, among others, soybeans, mushrooms, tangerines and whole wheat pitta bread.[102]

Due to lack of evidence, no country has published a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for choline, which is a vitamin-like essential nutrient. The Australian, New Zealand, and European Union national nutrition bodies note there have been no reports of choline deficiency in the general population.[105] There are, however, Adequate Intakes such as the European Union's number of 400 mg/day for adults, and the US's number of 425 mg/day for adult non-pregnant women and 550 mg/day for adult men. An Adequate Intake is a level assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy, established when evidence is insufficient to develop an RDA[106] (see Dietary Reference Intake).

Choline deficiency, as created in lab conditions, can lead to health problems such as liver damage, a result of liver cells initiating programmed cell death (apoptosis), as well as an increase in neural tube defects in pregnant women.[104] In a study, 77% of men, 44% of premenopausal women, and 80% of postmenopausal women developed fatty liver or muscle damage due to choline deficiency, showing that subject characteristics regulate the dietary requirement.[107] There is also some evidence that choline is an anti-inflammatory, but further studies are needed to confirm/refute findings.[108] Many multivitamins do not contain the Adequate Intake of choline.[109]

The main function of vitamin D in the body is to enhance absorption of calcium for normal mineralization of bones and calcium-dependent tissues.[33]

Sunlight, fortified foods, and dietary supplements are the main sources of vitamin D for vegans. Humans produce vitamin D naturally in response to sun exposure and ultraviolet light (UV) acting on skin to stimulate vitamin D synthesis.[33] UV light penetrates the skin at wavelengths between 290 and 320 nanometers, where it is then converted into vitamin D3.[33] Vitamin D2 can be obtained from fungi, such as mushrooms exposed to sun or industrial ultraviolet light, offering a vegan choice for dietary or supplemental vitamin D.[110][111] Plant milks, such as from oat, soy, or almond, and breakfast cereals are commonly fortified with vitamin D.[33]

The recommended daily intake of vitamin D for adults is 600 IU (15 micrograms), and for adults over 70 years old, 800 IU (20 micrograms).[33]

Vitamin D comes in two forms. Cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is synthesized in the skin after exposure to the sun or consumed from food, usually from animal sources.[33] Ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) is derived from ergosterol from UV-exposed mushrooms or yeast.[33] When produced industrially as supplements, vitamin D3 is typically derived from lanolin in sheep wool. However, both provitamins and vitamins D2 and D3 have been discovered in various species of edible Cladina lichens (especially Cladina rangiferina).[112] These edible lichen are harvested in the wild for producing vegan vitamin D3.[113] Conflicting studies have suggested that the two forms of vitamin D may or may not be bioequivalent.[114] According to 2011 research from the U. S. National Academy of Medicine (then called Institute of Medicine), the differences between vitamins D2 and D3 do not affect metabolism, both function as prohormones, and when activated, exhibit identical responses in the body.[115] Although vitamin D3 is produced in small amounts by lichens or algae exposed to sunlight,[116][117] industrial production in commercial quantities is limited, and there are few supplement products as of 2019.[118]

HOW TO BECOME OPTIMALLY HAPPY, HEALTHY & WEALTHY

We meet every Sunday 3 pm sharp at 138 Saint James Place BKLYN, NY 11238.

You must RSVP by calling 718-783-3465 in order to attend.

1.) How to become optimally happy.

Happiness is a choice.

Choose to be happy.

Have an attitude of gratitude that you are still breathing.

Choose to be happy from within no what are your circumstances are in the present moment.

List your life's purposes & top 5 passions in life and start spending much more time doing your life's purposes & your passions in life.

Google the benefits of Spiritual Enlightenment & how to achieve Spiritual Enlightenment, print the information, study it then practice whatever you learned.

Be around other happy people, spend time in nature & visit places, do activities, embrace thoughts & emotions that brings you bliss & joy.

2.) How to become optimally healthy.

Maintain a positive mental attitude no matter the circumstances.

Become an organic alkaline raw vegan, if you cannot do 100% raw then do at least 80% raw vegan.

Get the book Raw food made easy for 1 or 2 people by Jennifer Cornbleet and see her videos on youtube.com. We prepare raw vegan cuisine every Sunday 3 pm 138 Saint James Place BKLYN, NY 11238 RSVP BY CALLING 718-783-3465.

Exercise at least every other day a half hour or more, bare minimum.

Google examples of cardio, strength training, stretching & balancing exercises.

Go to youtube.com to learn about the Tibetan 5 rites & Rebounding exercises and Google their benefits.

Make sure your exercise program includes all 4 types of exercises and try the Tibetan 5 Rites & rebounding exercises.

3.) How to become optimally wealthy.

Invest in yourself, life's purposes & passions financially.

Prioritize needs before desires and assets before liabilities.

Create multiple sources of income based upon your life's purposes & passions.

Learn to save as much as possible and create passive sources of income.

It is better to have your assets create money for you rather than you spending a lifetime trading hours for dollars while hating what you do in order to create the dollars which is never enough.

Summary:

Most people squander their health in search of wealth [never achieving true wealth], only to later squander their wealth [whatever little they saved, if any, most individuals are in debt, debt = slavery] in search of health.

90% of people do not like their JOBS = JUST OVER BROKE!

90% OF THE PEOPLE ON THE PLANET ARE NOT HAPPY.

There is a better way.

Google, youtube.com, print, study & practice the following information below.

A.) 11 different types of motivation and see which ones are inspiring to you.

B.) 7 habits of highly effective people.

C.) Become principle-centered & solution-oriented.

D.) Write your mission statement & your vision statement and read it every morning before you start your day along with your positive affirmations, prayers and / or chanting "OM".

E.) The 5 agreements.

F.) 8 levels of Maslow's needs and desires.

G.) The benefits of the raw vegan lifestyle and what is the raw vegan lifestyle?

H.) Examples of 4 prong exercises - cardio, strength training, stretching, balancing & Tibetan 5 Rites & Rebounding exercises.

I.) The best nutritional, herbal supplementation and free health information

WWW.HERBDOC.COM?RFSN=1044625.OBOCB

J.) Eating documentary by Mike Anderson and the original Secret documentary by Rhonda Byrne on youtube.com

K.) Any video by Dr. Richard Schulze of American Botanical Pharmacy on youtube.com.

L.) Maximum Achievement of your goals and Accumulation of riches by Brian Tracy.

Call Dr. Natural for the 30 steps to a happy, healthy & wealthy life and for the best books, DVDs, CDs, Charts on creating optimal happiness, health & wealth call Dr. Natural 718-783-3465 and join www.templeofillumination.ning.com

Please forward this information to everyone you know.

This simple information SAVES LIVES!

Sunday, August 8, 2021

7:00 pm - 8:30 pm (Doors open 5:00 pm)

SummerStage, Central Park

Rumsey Playfield, Manhattan 10021

Tickets are no longer required for free performances at SummerStage. All free performances will be open to the public, first come, first served, with limited capacity, and will continue to follow CDC recommendations. Visit here for more information.

5 PM – Doors

6 PM – Rooftop Films Summer Series Films (see below)

7 PM – Performance

This performance will be livestreamed on SummerStageAnywhere.org.

—

One of New York’s iconic cultural institutions, the Metropolitan Opera returns to Central Park for its 12th year of SummerStage concerts with a performance on August 8. Met stars Leah Hawkins, Paul Appleby, and Will Liverman present an enchanting program of arias and duets from some of opera’s most beloved works, accompanied by Bryan Wagorn on piano.

Leah Hawkins, soprano (photo credit: Arielle Doneson)

A graduate of the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program, soprano Leah Hawkins made her Met debut during the 2018–19 season as an Alms Collector in Suor Angelica and has since taken the stage as the Priestess in Aida, Strawberry Woman in Porgy and Bess, and Masha in The Queen of Spades. She began her 2020–21 season as Desdemona in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas at the Bavarian State Opera, with later appearances at Portland Opera, Tulsa Opera, and the Elbphilharmonie Hamburg. She recently completed the Cafritz Young Artist Program at Washington National Opera, where she sang the Heavenly Voice in Don Carlo, Cousin Blanche / Sadie Griffith in Terence Blanchard’s Champion, and Mrs. Dorsey / Amelia Boynton in the premiere of the revised version of Philip Glass’s Appomattox, among others. On the concert stage, she has appeared with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Colorado Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, and Yale Philharmonia.

Paul Appleby, tenor (photo credit: Jonathan Tichler)

Hailing from South Bend, Indiana, tenor Paul Appleby was a winner in the 2009 National Council Auditions, later participating in the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. He made his company debut in 2011 as Brighella in Ariadne auf Naxos and has since given memorable performances in Don Giovanni, Pelléas et Mélisande, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, The Rake’s Progress, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Nico Muhly’s Two Boys, Dialogues des Carmélites, Les Troyens, and The Enchanted Island. He will return during the 2021–22 season as David in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Grimoaldo in Rodelinda. In recent seasons, he has also appeared at Houston Grand Opera, Dutch National Opera, San Francisco Opera, the Paris Opera, Glyndebourne Festival, and the Santa Fe Opera and in concert with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra of St. Luke’s, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among others.

Will Liverman, baritone (photo credit: Larrynx Photography)

Virginia-born baritone Will Liverman first appeared at the Met in 2018 as Malcolm Fleet in the North American premiere of Nico Muhly’s Marnie, returning the next season as Horemhab in Philip Glass’s Akhnaten and Papageno in The Magic Flute. During the company’s highly anticipated 2021–22 season, he will star as Charles in the opening-night, Met-premiere performance of Terrence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones and reprise his celebrated portrayals of Papageno and Horemhab. Elsewhere, he will sing the Count in Le Nozze di Figaro at Austin Opera and Charles at Lyric Opera of Chicago. In past years, he has appeared at Opera Colorado, Opera Philadelphia, the Santa Fe Opera, the Dallas Opera, Tulsa Opera, Central City Opera, Kentucky Opera, Seattle Opera, and Virginia Opera, among others. He originated the role of Dizzy Gillespie in Daniel Schnyder’s Charlie Parker’s Yardbird at Opera Philadelphia, a role which he also sang at English National Opera, New York’s Apollo Theater, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Madison Opera.

Bryan Wagorn, piano (photo credit: Dario Acosta)

Canadian pianist Bryan Wagorn joined the Metropolitan Opera music staff as an assistant conductor in 2013, serves on the faculty of Mannes College of Music, and regularly performs throughout North America, Europe, and Asia as soloist, chamber musician, and recital accompanist to the world’s leading singers and instrumentalists. He is also a graduate of the Met’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program. He has appeared on major television and radio stations, including ABC’s Good Morning America, WQXR, and CBC Radio; has performed in recital for the George London Foundation, Marilyn Horne Foundation, and Richard Tucker Foundation; and collaborated with Angel Blue, Joyce DiDonato, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Isabel Leonard, Karita Mattila, Eric Owens, Ailyn Pérez, Nadine Sierra, Carol Wincenc, Pinchas Zukerman, the New York Woodwind Quintet, and members of the Met Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, and Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He also performed as pianist in the Met’s Grammy-winning recording of Porgy and Bess.

Community Gardens (Kolektyviniai sodai)

Community Gardens (Kolektyviniai sodai)

Vytautas Katkus, Lithuania

Patriarchal masculinity seems to catch its last breath in the sun.

The Lamb of God (O Cordeiro De Deus)

The Lamb of God (O Cordeiro De Deus)

David Pinheiro Vicente, Portugal, France

The summer festivities of a Portuguese village are suffused with sensuality and violence in this enigmatic portrait of a tightly knit family.

What is spiritual enlightenment? Is a complete understanding of life and the Universe.

A detachment of all things impermanent and a complete awareness of everything that is at the moment that it is without thinking about the past and the future.

Spiritual Enlightenment is when someone self realizes who he is and who is not.

The top 15 methods to achieve spiritual enlightenment

1* Meditation: needs to calm the mind and bring conscious attention to oneself. Shut down external distraction to reduce internal distraction. To be honest with yourself

2 * Practice Yoga: will help to unite with the Divine

3* Chanting: To align internal spiritual energy with the Divine.

4* Pray: listening for God on a contemplative silence

5* Fasting: to rely on spiritual sustenance of God rather than physical sustenance of food

6* Dancing, Shaking, Quaking to excess: can initiate the cessation of conscious thought and connect with the source; that catalyzes the enlightenment experience.

7* Pilgrimage’s: visiting a spiritual retreat help to reduce the mind’s sense of self

8* Near death experience: brain shutting down and conscious thought ceased

9* Martial art: allows the mind to quiet and be focused into the body, thereby reducing the body thought

10* Sensory deprivation tank: to cut off from as many sensory distractions as to be able to enter a deep meditation state

11* Depression: we are one step away from thinking of nothing when psychological pain becomes too much to bare

12* Sweat lodges: the body falls into distress then the thought in the brain decreases and becomes less patterned bringing the mind into a much more focused state

13* Embrace your fears: by not allowing fear to control you by destabilizing your mind and preventing you from taking action on the things you want to or should do

14* Taking psychedelic or mushrooms or marijuana

15* Spontaneous enlightenment

One love❤EVENTS FOR TONITE CALL DR. NATURAL AT LET ME KNOW WHICH ONES STRIKES YOUR INTERESTS 718-783-3465 / 347-760-8147

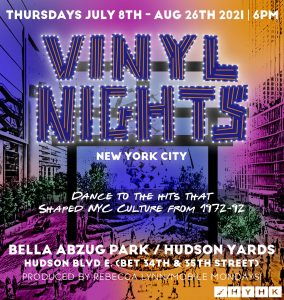

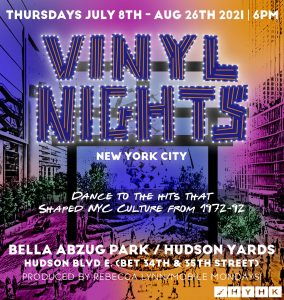

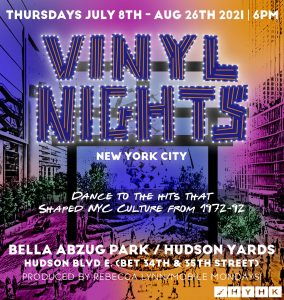

6 PM OUTDOOR PARTY AT BELLA ABZUG PARK NEAR HUDSON YARDS MUSIC FROM 1972 - 1992.

7 PM THE FILM CROOKLYN SHOWING AT 650 FULTON ST BKLYN

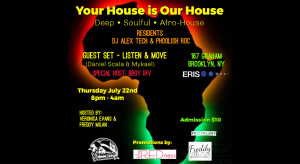

8 PM INDOOR BASEMENT PARTY 167 GRAHAM AVE

8 PM AND 10 PM LIVE PERFORMANCES SHOWS WITH MUSIC INDOOR AND OUTDOOR 290 MESEROLE ST BKLYN

|

Wednesday 07/21 04:00 PM |

New York City |

FREE |

|

Wednesday 07/21 05:00 PM |

New York City Military Park |

FREE |

|

Wednesday 07/21 07:00 PM |

New York City Grant's Tomb |

|

Wednesday 07/21 08:00 PM |

New York City Otto's Shrunken Head |

FREE |

|

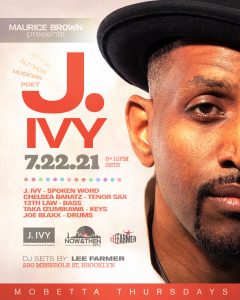

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Eris |

FREE |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/22 12:00 PM |

New York City Ravel Penthouse Rooftop |

|

Thursday 07/22 06:00 PM |

New York City Bella Abzug Park at Hudson Yards |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Eris |

FREE |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/22 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

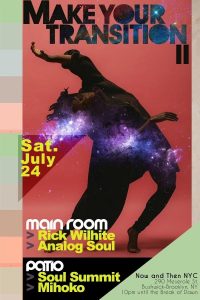

Thursday 07/22 07:00 PM |

New York City Now & Then NYC |

|

Friday 07/23 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/23 04:30 PM |

New York City |

|

Friday 07/23 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Friday 07/23 07:00 PM |

New York City Yonkers Downtown Waterfront |

|

Friday 07/23 06:00 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Friday 07/23 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

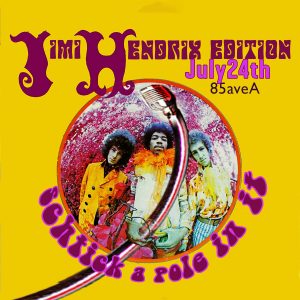

Saturday 07/24 05:00 PM |

New York City Summerstage in Central Park |

|

Saturday 07/24 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Saturday 07/24 10:00 PM |

New York City The Sultan Room |

|

Saturday 07/24 07:00 PM |

New York City SummerStage at Central Park |

|

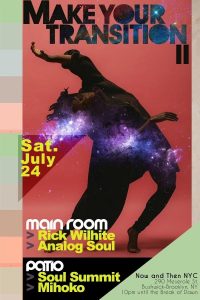

Saturday 07/24 10:00 PM |

New York City Now & Then NYC |

|

Saturday 07/24 05:00 PM |

New York City Summerstage in Central Park |

|

Saturday 07/24 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Saturday 07/24 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Saturday 07/24 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

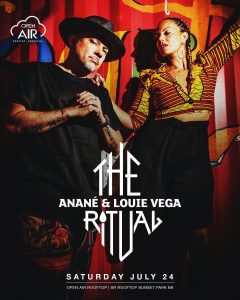

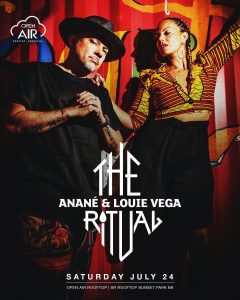

Saturday 07/24 10:00 PM |

New York City SR Rooftop |

|

Sunday 07/25 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Sunday 07/25 02:00 PM |

New York City Snug Harbor |

|

Sunday 07/25 03:00 PM |

New York City Radial Park |

|

Sunday 07/25 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Sunday 07/25 02:00 PM |

New York City Snug Harbor |

|

Monday 07/26 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Monday 07/26 12:00 AM |

New York City |

|

Monday 07/26 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

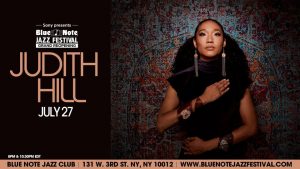

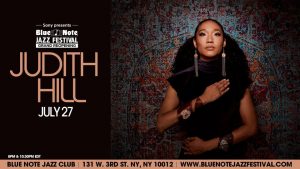

Tuesday 07/27 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Tuesday 07/27 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Tuesday 07/27 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 07:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Wednesday 07/28 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 07:00 PM |

New York City Grant's Tomb |

|

Wednesday 07/28 07:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Thursday 07/29 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/29 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/29 07:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Friday 07/30 06:00 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

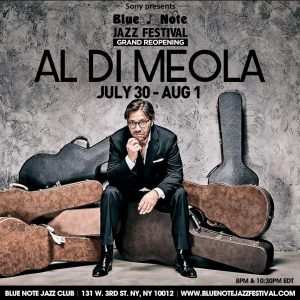

Friday 07/30 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/30 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/30 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/30 04:00 PM |

New York City Hotel RL/The Living Stage |

|

Friday 07/30 07:00 PM |

New York City Marcus Garvey Memorial Park |

|

Friday 07/30 07:30 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

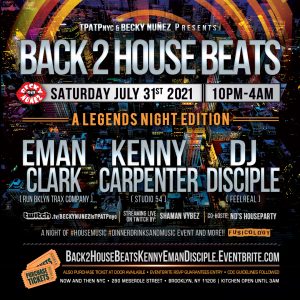

Saturday 07/31 10:00 PM |

New York City Now & Then NYC |

|

Saturday 07/31 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Saturday 07/31 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Saturday 07/31 06:00 PM |

New York City Prospect Park Bandshell |

|

Saturday 07/31 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Free raw vegan preparation demonstration

every Sun. 3 pm

RSVP 718-783-3465

Temple of Illumination 138 Saint James Place BKLYN, NY 11238

|

|

Monday 07/19 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Monday 07/19 11:00 AM |

New York City |

FREE |

|

Wednesday 07/21 05:00 PM |

New York City Military Park |

FREE |

|

Wednesday 07/21 07:00 PM |

New York City Grant's Tomb |

|

Wednesday 07/21 08:00 PM |

New York City Otto's Shrunken Head |

FREE |

|

Thursday 07/22 12:00 PM |

New York City Ravel Penthouse Rooftop |

|

Thursday 07/22 06:00 PM |

New York City Bella Abzug Park at Hudson Yards |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Eris |

FREE |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/22 12:00 PM |

New York City Ravel Penthouse Rooftop |

|

Thursday 07/22 06:00 PM |

New York City Bella Abzug Park at Hudson Yards |

|

Thursday 07/22 08:00 PM |

New York City Eris |

|

Friday 07/23 06:00 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Friday 07/23 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/23 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/23 04:30 PM |

New York City |

|

Friday 07/23 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Friday 07/23 07:00 PM |

New York City Yonkers Downtown Waterfront |

|

Saturday 07/24 07:00 PM |

New York City SummerStage at Central Park |

|

Saturday 07/24 07:00 PM |

New York City SummerStage at Central Park |

|

Saturday 07/24 05:00 PM |

New York City Summerstage in Central Park |

|

Saturday 07/24 10:00 PM |

New York City Now & Then NYC |

|

Saturday 07/24 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Saturday 07/24 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Saturday 07/24 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Saturday 07/24 10:00 PM |

New York City SR Rooftop |

|

Saturday 07/24 11:45 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Saturday 07/24 08:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Sunday 07/25 02:00 PM |

New York City Snug Harbor |

|

Sunday 07/25 02:00 PM |

New York City Snug Harbor |

|

Sunday 07/25 07:00 PM |

New York City SummerStage at Central Park |

|

Sunday 07/25 06:00 PM |

New York City SR Rooftop |

|

Monday 07/26 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Monday 07/26 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Tuesday 07/27 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Tuesday 07/27 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Wednesday 07/28 07:00 PM |

New York City Grant's Tomb |

|

Wednesday 07/28 07:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Thursday 07/29 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/29 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Thursday 07/29 07:00 PM |

New York City Drom |

|

Friday 07/30 06:00 PM |

New York City SkyPort Marina |

|

Friday 07/30 08:00 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/30 10:30 PM |

New York City Blue Note |

|

Friday 07/30 04:00 PM |

New York City Hotel RL/The Living Stage |

|

Friday 07/30 07:00 PM |

New York City Marcus Garvey Memorial Park |

|

Friday 07/30 07:30 PM |

New York City Drom |

Tue, July 20, 2021

6 - 8 PM EST

Rome Neal Banana Puddin' Jazz

Supported by Jazz Foundation of America

Presents

"JAZZ Live in the Commodore Barry Park" (Brooklyn)

Bring your folding chairs, blankets...

Complimentary Banana Puddin' (as long as it lasts!)

Featuring

Chip Crawford (keys), Patience Higgins (sax)

Dwayne Cook Broadnax (drums), Lonnie Plaxico (bass)

And the Vocals of

Patsy Grant, Frank Senior, Steve Cromity

A FREE Virtually Live Streamed!

Youtube and FB Live

ULTIMATE CALENDAR OF EVENTS RSVP DR. NATURAL 718-783-3465

JOIN WWW.TEMPLEOFILLUMINATION.NING.COM ;

SUMMER CLEANSE & DETOX PROGRAM BEGINS NOW.

LEARN HOW TO BUILD YOUR IMMUNE SYSTEM NATURALLY.

JOBS, ROOMS, FREE CLOTHES, SHOES, SNEAKERS, FURNITURE, HOUSEWARES, VEGAN FOOD, RAW VEGAN PREPARATION DEMONSTRATIONS

EVERY SUN. 9 AM - 10 AM PROSPECT PARK GROUP RUN NY FLYERS RUNNING GROUP

EVERY SUN. 11 AM - 6 PM A TASTE OF AFRICA SQUARE - AN OUTDOOR EVENT ON TOMPKINS BETWEEN PUTNAM & MADISON AVE BKLYN

EVERY SUN. 3 PM FREE RAW VEGAN PREPARATION DEMONSTRATION, SUMMER CLEANSE & DETOX ORIENTATION & TRAINING TO BECOME A NATURAL HEALER

EVERY THURS. 2 PM - 9 PM OUTDOOR DAY PARTY VON KING PARK BKLYN

EVERY THURS. 6 PM - 9 PM OUTDOOR PARTY BELLA ABZUG PARK NYC

EVERY THURS. 5 PM - 1 AM AFROHOUSE MUSIC 167 GRAHAM AVE BKLYN

EVERY THURSDAY 6 PM - 7 PM BROOKLYN 5K RUN THROUGH THE STREETS OF BEDSTUY STARTING POINT IS VON KING PARK IN BKLYN

EVERY FRIDAY 4 PM - 9 PM OUTDOOR DAY PARTY AT VON KING PARK BKLYN

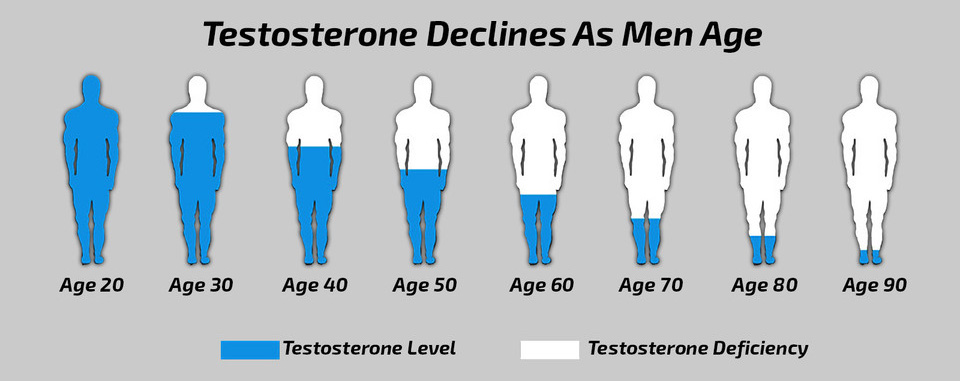

Step 1: Boost Your Free Testosterone Levels

Testosterone is central in the male sexual response, including the desire for sex and the mechanics of triggering an erection. High levels of testosterone are associated with a strong desire for sex and an increased ability to have an erection.1, 2

Step 2: Increase Blood Flow To Your Penis

A better blood flow means that the cavities in your penis will fill up with blood more readily. This counters the effects of weak erections. You gain the power to have an erection on demand, maintain it for longer and experience better sex.*

Step 3: Improve Your Libido & Sexual Stamina

There are some ingredients that will improve the mood and desire for sex. These have long been known as aphrodisiacs in traditional Chinese medicine, products that include these ingredients may increase your sex drive and libido which does drop in men at a certain age.*

Last Manhattanhenge of 2021 Arrives Tonight. But Will the Skies Be Clear Enough to See?

If you’re wondering what exactly Manhattanhenge is, it is a solar phenomenon that happens twice a year when the sun aligns perfectly with the midtown Manhattan street grid.

The best area to witness Manhattanhenge is along wide and clear cross streets in Manhattan, including:

14th Street

23rd Street

34th Street

42nd Street

57th Street

More than that, alternative treatments such as herbal medicine focus on prevention and treating underlying problems, not just symptoms.

Herbal medicine involves the use of plants and extracts to deliver effective and safe treatments. Even Western medical practitioners are not only stopping to take note, but starting to suggest natural alternative treatments as well.

For instance, it used to be that kidney stone patients could only take medication or have surgery to remove a painful stone. Now, it is recognized that lemon is effective in breaking down stones.

Herbal medicine, Phytotherapy, or Herbalism, as it is also known, is now used often in lieu of Western medicine. It is very popular for prevention and treatment of illness and health issues. Botanical medicine or medical Herbalism systems of treatment reach back to Herbalism found in traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic Herbalism, and even in Western Herbalism.

Herbal medicine is older than Western medicine and has some long-standing treatments and cures that have lasted for thousands of years because they work.

As it turns out, it is not just in the mind of the user or practitioners. It turns out that smart, modern scientists have tested the long-standing herbal remedies to find out what makes them work. Plants contain some very powerful components and chemicals that re-balance the body. In general, herbal remedies can be prepared as a liquid or powder extracts, tablets, essential oils, teas, and ointments.

Because the herbal remedies work with the body’s processes to heal, they are generally safer than prescription drugs and surgery, and a lot more affordable. The benefits of herbal treatments are listed below and include everything from effective treatments for colds, cancer, and even diabetes.

Because herbal medicine works with the body’s natural self-healing capabilities, it actually enhances biological healing to quicken the recovery process. It also means that the body’s own internal environment is maintained during recovery rather than ravaged, which doctors say, antibiotics do to the body. In the case of Western antibiotics, the individual often feels “off” in their stomach after dealing with the healing that antibiotics cause. It turns out that their stomach, then has to heal as well.

With herbal remedies, the body is maintained, not partly destroyed and requiring rebuilding after the treatment is taken. What many people do not know is that herbs are powerful enough to stimulate glands to re-balance hormones by re-initiating hormone production. Hormones play a role of the signal to tell the body to increase or reduce biological processes.

Many herbal remedies have a set of rules to follow to improve their ability to work. For instance, while the person increasing their lemon water intake to reduce kidney stones is treating stones, they would also eliminate foods that allow kidney stones to be produced. The idea is to support the body in its healing. The changes at some point become a habit to prevent future re-occurrences of the issue.

As it turns out, herbs strengthen the immune system’s functioning to build the body’s defenses naturally. This prevents primary and secondary infection.

Building an immune system that is stronger while bringing in a holistically regulated diet improves metabolism. That leads to optimal absorption from the diet nutrition. Once people start on a healthy path they are less likely to want junk food, because it is one way to erase the good effects of using herbal medicine. Junk food robs the body of health by harming its ability to take in nutrients while packing on unnecessary weight.

Good wholesome nutrition improves treatment, while strengthening the body’s immune system. Medicinal herbs work better when they have the added support of a well-fed body. It improves the efficacy of treatments.medicinal plants and their uses

People can have allergies to anything, especially medications, food, and even herbal remedies. Herbal medicine means that there is a potential for side-effects and allergies. They do work as the body is meant to operate, and that is where the herbal medicine has advantages of Western medicine.

Yet, with herbal medication, there are generally fewer problems than with pharmaceuticals because the chemical element of foreign substances in the body are not part of the equation. It is easier for the body to heal with herbal medicine.

Now herbal remedies are administered by practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Naturopathy, or other alternative practices. Naturopaths, for one, go to school for years post-graduate, just like a medical doctor or chiropractor might. They learn all about the plants, their makeup, how they need to be prepared, and dosing for different sized people and their problems. It makes sense to turn to the experts on plants instead of trying to self-medicate because people can have bad allergies to herbal remedies.

In the United States, ginseng and bee pollen remain very popular along with black cohosh, cat’s claw among many others. Ephedra is one herbal remedy that most people have heard of because it is an appetite suppressant. It treats bronchitis and asthma as well. Meanwhile, echinacea boosts the immune system. Kava kava has also remained popular, and it treats anxiety.

Ginkgo improves blood circulation and oxygenation to boost memory and concentration. People who have trouble sleeping often like the calming effect of valerian. It is a natural muscle relaxant with a mild effect.

The list of favorable blood sugar herbal supplements is a long one. It includes cinnamon, ginkgo biloba, blueberry leaves, bitter melon, garlic, onion, fenugreek, and goat’s rue just to name some. They are all helpful at controlling blood sugar levels to help lower a diabetic’s reliance on insulin. The underlying action is that these herbal remedies increase the body’s insulin secretion to keep the body’s blood sugar levels balanced.

Nettles are one of the favorites for dealing with particular allergies, along with quercetin, the ephedra, butterbur, and Astragalus work to combat different types of allergies by controlling the body’s anti-histamines. They also include antioxidants and anti-inflammatories. They can treat skin problems and asthma as well, such as acne and eczema.

Colon cleanses are important to keep the body’s intestinal tract clean to prevent colon cancer. Plantago psyllium seed, which is part of many products available at the supermarket, plays a role as a colon cleanser. Others that work their magic in the colon include rhubarb powder, aloe vera, and alfalfa juice. Chlorella, which is often found in “green juices” combined with the power of carrot concentrate, and garlic all are powerful colon cleansers. They clean and improve digestion in the intestinal tract. The colon itself does not uptake nutrients, it is more akin to a waste chute.

Heart and blood-related functions are treated with garlic, ginkgo, and ginger. Know that there are a multitude of options not mentioned here. Hawthorn cuts blood pressure while dilates blood vessels to support a stronger heart. Garlic treats coronary artery disease while improving cholesterol levels. Ginkgo biloba even helps with the treatment of cerebrovascular diseases.

Herbal medicines are effective for weight loss to reduce obesity. Herbal medications are often appetite suppressants, stimulants, diuretics, and cathartics. Commonly fennel, flaxseed, phyllium, alfalfa, senna, nettle, kola nut, and hawthorn are used to aid in weight loss. They also work to improve health improvement to help with overall health.

Various herbs are increasingly turned to treat both minor and major health issues from the common cold to sleep problems. Even allergies, diabetes, heart and blood pressure can be regulated through the use of herbal remedies. Treating anxiety, heart problems, breathing problems, and skin disorders take well to herbal remedies. All different parts of plants are used to create herbal remedies that help people to improve their health and well-being for today and into the future.

More than that, alternative treatments such as herbal medicine focus on prevention and treating underlying problems, not just symptoms.

Herbal medicine involves the use of plants and extracts to deliver effective and safe treatments. Even Western medical practitioners are not only stopping to take note, but starting to suggest natural alternative treatments as well.

For instance, it used to be that kidney stone patients could only take medication or have surgery to remove a painful stone. Now, it is recognized that lemon is effective in breaking down stones.

Herbal medicine, Phytotherapy, or Herbalism, as it is also known, is now used often in lieu of Western medicine. It is very popular for prevention and treatment of illness and health issues. Botanical medicine or medical Herbalism systems of treatment reach back to Herbalism found in traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic Herbalism, and even in Western Herbalism.

Herbal medicine is older than Western medicine and has some long-standing treatments and cures that have lasted for thousands of years because they work.

As it turns out, it is not just in the mind of the user or practitioners. It turns out that smart, modern scientists have tested the long-standing herbal remedies to find out what makes them work. Plants contain some very powerful components and chemicals that re-balance the body. In general, herbal remedies can be prepared as a liquid or powder extracts, tablets, essential oils, teas, and ointments.

Because the herbal remedies work with the body’s processes to heal, they are generally safer than prescription drugs and surgery, and a lot more affordable. The benefits of herbal treatments are listed below and include everything from effective treatments for colds, cancer, and even diabetes.

Because herbal medicine works with the body’s natural self-healing capabilities, it actually enhances biological healing to quicken the recovery process. It also means that the body’s own internal environment is maintained during recovery rather than ravaged, which doctors say, antibiotics do to the body. In the case of Western antibiotics, the individual often feels “off” in their stomach after dealing with the healing that antibiotics cause. It turns out that their stomach, then has to heal as well.

With herbal remedies, the body is maintained, not partly destroyed and requiring rebuilding after the treatment is taken. What many people do not know is that herbs are powerful enough to stimulate glands to re-balance hormones by re-initiating hormone production. Hormones play a role of the signal to tell the body to increase or reduce biological processes.

Many herbal remedies have a set of rules to follow to improve their ability to work. For instance, while the person increasing their lemon water intake to reduce kidney stones is treating stones, they would also eliminate foods that allow kidney stones to be produced. The idea is to support the body in its healing. The changes at some point become a habit to prevent future re-occurrences of the issue.

As it turns out, herbs strengthen the immune system’s functioning to build the body’s defenses naturally. This prevents primary and secondary infection.

Building an immune system that is stronger while bringing in a holistically regulated diet improves metabolism. That leads to optimal absorption from the diet nutrition. Once people start on a healthy path they are less likely to want junk food, because it is one way to erase the good effects of using herbal medicine. Junk food robs the body of health by harming its ability to take in nutrients while packing on unnecessary weight.

Good wholesome nutrition improves treatment, while strengthening the body’s immune system. Medicinal herbs work better when they have the added support of a well-fed body. It improves the efficacy of treatments.medicinal plants and their uses

People can have allergies to anything, especially medications, food, and even herbal remedies. Herbal medicine means that there is a potential for side-effects and allergies. They do work as the body is meant to operate, and that is where the herbal medicine has advantages of Western medicine.

Yet, with herbal medication, there are generally fewer problems than with pharmaceuticals because the chemical element of foreign substances in the body are not part of the equation. It is easier for the body to heal with herbal medicine.

Now herbal remedies are administered by practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Naturopathy, or other alternative practices. Naturopaths, for one, go to school for years post-graduate, just like a medical doctor or chiropractor might. They learn all about the plants, their makeup, how they need to be prepared, and dosing for different sized people and their problems. It makes sense to turn to the experts on plants instead of trying to self-medicate because people can have bad allergies to herbal remedies.

In the United States, ginseng and bee pollen remain very popular along with black cohosh, cat’s claw among many others. Ephedra is one herbal remedy that most people have heard of because it is an appetite suppressant. It treats bronchitis and asthma as well. Meanwhile, echinacea boosts the immune system. Kava kava has also remained popular, and it treats anxiety.

Ginkgo improves blood circulation and oxygenation to boost memory and concentration. People who have trouble sleeping often like the calming effect of valerian. It is a natural muscle relaxant with a mild effect.

The list of favorable blood sugar herbal supplements is a long one. It includes cinnamon, ginkgo biloba, blueberry leaves, bitter melon, garlic, onion, fenugreek, and goat’s rue just to name some. They are all helpful at controlling blood sugar levels to help lower a diabetic’s reliance on insulin. The underlying action is that these herbal remedies increase the body’s insulin secretion to keep the body’s blood sugar levels balanced.

Nettles are one of the favorites for dealing with particular allergies, along with quercetin, the ephedra, butterbur, and Astragalus work to combat different types of allergies by controlling the body’s anti-histamines. They also include antioxidants and anti-inflammatories. They can treat skin problems and asthma as well, such as acne and eczema.

Colon cleanses are important to keep the body’s intestinal tract clean to prevent colon cancer. Plantago psyllium seed, which is part of many products available at the supermarket, plays a role as a colon cleanser. Others that work their magic in the colon include rhubarb powder, aloe vera, and alfalfa juice. Chlorella, which is often found in “green juices” combined with the power of carrot concentrate, and garlic all are powerful colon cleansers. They clean and improve digestion in the intestinal tract. The colon itself does not uptake nutrients, it is more akin to a waste chute.

Heart and blood-related functions are treated with garlic, ginkgo, and ginger. Know that there are a multitude of options not mentioned here. Hawthorn cuts blood pressure while dilates blood vessels to support a stronger heart. Garlic treats coronary artery disease while improving cholesterol levels. Ginkgo biloba even helps with the treatment of cerebrovascular diseases.

Herbal medicines are effective for weight loss to reduce obesity. Herbal medications are often appetite suppressants, stimulants, diuretics, and cathartics. Commonly fennel, flaxseed, phyllium, alfalfa, senna, nettle, kola nut, and hawthorn are used to aid in weight loss. They also work to improve health improvement to help with overall health.

Various herbs are increasingly turned to treat both minor and major health issues from the common cold to sleep problems. Even allergies, diabetes, heart and blood pressure can be regulated through the use of herbal remedies. Treating anxiety, heart problems, breathing problems, and skin disorders take well to herbal remedies. All different parts of plants are used to create herbal remedies that help people to improve their health and well-being for today and into the future.

This Raw Mac and Cheese is made with a cashew-based cream sauce that is both creamy and light. It’s seriously the best tasting macaroni and cheese out there, super easy, both you and your kids will adore!

More than that, alternative treatments such as herbal medicine focus on prevention and treating underlying problems, not just symptoms.

Herbal medicine involves the use of plants and extracts to deliver effective and safe treatments. Even Western medical practitioners are not only stopping to take note, but starting to suggest natural alternative treatments as well.

For instance, it used to be that kidney stone patients could only take medication or have surgery to remove a painful stone. Now, it is recognized that lemon is effective in breaking down stones.

Herbal medicine, Phytotherapy, or Herbalism, as it is also known, is now used often in lieu of Western medicine. It is very popular for prevention and treatment of illness and health issues. Botanical medicine or medical Herbalism systems of treatment reach back to Herbalism found in traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic Herbalism, and even in Western Herbalism.

Herbal medicine is older than Western medicine and has some long-standing treatments and cures that have lasted for thousands of years because they work.

As it turns out, it is not just in the mind of the user or practitioners. It turns out that smart, modern scientists have tested the long-standing herbal remedies to find out what makes them work. Plants contain some very powerful components and chemicals that re-balance the body. In general, herbal remedies can be prepared as a liquid or powder extracts, tablets, essential oils, teas, and ointments.

Because the herbal remedies work with the body’s processes to heal, they are generally safer than prescription drugs and surgery, and a lot more affordable. The benefits of herbal treatments are listed below and include everything from effective treatments for colds, cancer, and even diabetes.

Because herbal medicine works with the body’s natural self-healing capabilities, it actually enhances biological healing to quicken the recovery process. It also means that the body’s own internal environment is maintained during recovery rather than ravaged, which doctors say, antibiotics do to the body. In the case of Western antibiotics, the individual often feels “off” in their stomach after dealing with the healing that antibiotics cause. It turns out that their stomach, then has to heal as well.

With herbal remedies, the body is maintained, not partly destroyed and requiring rebuilding after the treatment is taken. What many people do not know is that herbs are powerful enough to stimulate glands to re-balance hormones by re-initiating hormone production. Hormones play a role of the signal to tell the body to increase or reduce biological processes.

Many herbal remedies have a set of rules to follow to improve their ability to work. For instance, while the person increasing their lemon water intake to reduce kidney stones is treating stones, they would also eliminate foods that allow kidney stones to be produced. The idea is to support the body in its healing. The changes at some point become a habit to prevent future re-occurrences of the issue.

As it turns out, herbs strengthen the immune system’s functioning to build the body’s defenses naturally. This prevents primary and secondary infection.

Building an immune system that is stronger while bringing in a holistically regulated diet improves metabolism. That leads to optimal absorption from the diet nutrition. Once people start on a healthy path they are less likely to want junk food, because it is one way to erase the good effects of using herbal medicine. Junk food robs the body of health by harming its ability to take in nutrients while packing on unnecessary weight.

Good wholesome nutrition improves treatment, while strengthening the body’s immune system. Medicinal herbs work better when they have the added support of a well-fed body. It improves the efficacy of treatments.medicinal plants and their uses

People can have allergies to anything, especially medications, food, and even herbal remedies. Herbal medicine means that there is a potential for side-effects and allergies. They do work as the body is meant to operate, and that is where the herbal medicine has advantages of Western medicine.

Yet, with herbal medication, there are generally fewer problems than with pharmaceuticals because the chemical element of foreign substances in the body are not part of the equation. It is easier for the body to heal with herbal medicine.

Now herbal remedies are administered by practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Naturopathy, or other alternative practices. Naturopaths, for one, go to school for years post-graduate, just like a medical doctor or chiropractor might. They learn all about the plants, their makeup, how they need to be prepared, and dosing for different sized people and their problems. It makes sense to turn to the experts on plants instead of trying to self-medicate because people can have bad allergies to herbal remedies.

In the United States, ginseng and bee pollen remain very popular along with black cohosh, cat’s claw among many others. Ephedra is one herbal remedy that most people have heard of because it is an appetite suppressant. It treats bronchitis and asthma as well. Meanwhile, echinacea boosts the immune system. Kava kava has also remained popular, and it treats anxiety.

Ginkgo improves blood circulation and oxygenation to boost memory and concentration. People who have trouble sleeping often like the calming effect of valerian. It is a natural muscle relaxant with a mild effect.

The list of favorable blood sugar herbal supplements is a long one. It includes cinnamon, ginkgo biloba, blueberry leaves, bitter melon, garlic, onion, fenugreek, and goat’s rue just to name some. They are all helpful at controlling blood sugar levels to help lower a diabetic’s reliance on insulin. The underlying action is that these herbal remedies increase the body’s insulin secretion to keep the body’s blood sugar levels balanced.

Nettles are one of the favorites for dealing with particular allergies, along with quercetin, the ephedra, butterbur, and Astragalus work to combat different types of allergies by controlling the body’s anti-histamines. They also include antioxidants and anti-inflammatories. They can treat skin problems and asthma as well, such as acne and eczema.

Colon cleanses are important to keep the body’s intestinal tract clean to prevent colon cancer. Plantago psyllium seed, which is part of many products available at the supermarket, plays a role as a colon cleanser. Others that work their magic in the colon include rhubarb powder, aloe vera, and alfalfa juice. Chlorella, which is often found in “green juices” combined with the power of carrot concentrate, and garlic all are powerful colon cleansers. They clean and improve digestion in the intestinal tract. The colon itself does not uptake nutrients, it is more akin to a waste chute.

Heart and blood-related functions are treated with garlic, ginkgo, and ginger. Know that there are a multitude of options not mentioned here. Hawthorn cuts blood pressure while dilates blood vessels to support a stronger heart. Garlic treats coronary artery disease while improving cholesterol levels. Ginkgo biloba even helps with the treatment of cerebrovascular diseases.

Herbal medicines are effective for weight loss to reduce obesity. Herbal medications are often appetite suppressants, stimulants, diuretics, and cathartics. Commonly fennel, flaxseed, phyllium, alfalfa, senna, nettle, kola nut, and hawthorn are used to aid in weight loss. They also work to improve health improvement to help with overall health.

Various herbs are increasingly turned to treat both minor and major health issues from the common cold to sleep problems. Even allergies, diabetes, heart and blood pressure can be regulated through the use of herbal remedies. Treating anxiety, heart problems, breathing problems, and skin disorders take well to herbal remedies. All different parts of plants are used to create herbal remedies that help people to improve their health and well-being for today and into the future.